“Did you see what that sign said?”

Mona said nothing, her arms stubbornly crossed, sulking. She should know after three years together that Sterling wasn’t swayed by temper tantrums, especially those performed by people who were wrong.

He turned up the radio.

The chipboard sign he’d just passed—nailed up beneath the town sign, spray-painted with fuzzy black letters—had probably only been an announcement for a garage sale weekend or turkey dinner at the fire station. That was social hour in a small town. You didn’t see that in a wasteland like Philadelphia. He was angry at Mona suddenly, for making him move there. Cities were not his natural habitat.

Inside the town limits, Old River was a more rundown version of the quaint place Sterling had lived in from birth to thirteen. More litter than he expected, and odd things, too, like a lone shoe, a book—or was that a photo album?—an entire backpack. Quite a few houses had overgrown lawns.

More than quite a few, actually.

The center of town was as he remembered: two lanes of traffic, parallel rows of buildings constructed sometime in the mid-1800s, and one caution light. Butterfield’s Grocery, Quinlan’s Diner, and the West End Motel were still there; Twist and Shake was gone, as was the Pearl Street Movie Theater, but other businesses had taken their spots. Only three cars were parked on the side of the road. Every storefront was dark. Old River had never been a bustling place, but it had also never been this dead.

“Are all dinky little towns this quiet?” came Mona’s voice.

No, he thought. Something was off, and he’d felt it since they’d crossed the town line. He hadn’t seen anyone outside, even though the day was perfect for mowing a lawn or running through a sprinkler. Something had happened here, but not drugs or the aluminum plant closing, or the prison—big employers here, he remembered.

Old River didn’t have the look of slow decay, but quick abandonment.

He pulled over in front of the library, still in the old general store with its wide covered porch. He’d spent many days there, with his mother and sister. He walked up to the front window and rapped on the glass—the view inside was the same as his memory—but not a soul stirred.

“Stay in the car,” he told Mona.

“Obviously.”

Sterling walked down the center of the street—right down the yellow line, making the nine-year-old in him feel like a rebel—and not a car passed, not a door opened, not a voice called out.

“Hello!” he even yelled.

Only the wind responded.

It was like Old River wasn’t even real, but a snapshot plucked straight from his memory. Nearly every detail was the same. Everything was still. Not even a dog was barking—and a dog was always barking, somewhere. Even the day was perfect, as the weather often is in nice memories. The sky was the perfect shade of late summer blue and the light breeze smelled of leaves. But the quiet unnerved him. He only ever heard such quiet in the middle of the woods in the middle of the night, miles from any road.

“Hello!” he yelled again.

Across from where he stood was the grocery; he wondered if Winnie was still there, humming behind the register, oblivious to customers. He went to the door and shook it—freaked out now—but it was locked.

“Sterling…” Mona whined, about to say the obvious. Something was wrong, they needed to leave. He was already thinking it.

He rattled the door again—someone had to be here—and when no one answered, his stomach dropped into his boots and the restless ache of panic began to tighten in his chest, and he both needed to figure this out and to get the hell out Old River. Cupping his hands over his eyes, he pressed his face against the glass door and searched the gloom inside for any signs of movement…

“Sterling!”

The shelves were a mess—half-empty, cans on the floor, boxes ripped open, garbage everywhere.

Something dark and low to the ground darted from one shadow to the next. Sterling flinched, his brain forgetting that his body was in the street. That had to have been a mouse or something. He pressed his eyes against the glass again—

A dark body threw itself against the door.

Thud, scrape, thud, scrape—

Sterling stumbled back a few steps. He stood in the middle of the chipped sidewalk—he and his friends would spend hot summer days loitering there, bikes thrown in the patch of grass between building and cement, darting inside Butterfield’s for candy and soda and whatever else all afternoon; he could see their faces clear as day now; Griffin, Finn, Crosby—and stared down at the bottom few inches of the glass.

The creature was a familiar shape, with a rounded body disproportionate to its pointed head. It scratched at the door with needle claws, snarling. Did rats have fangs like that normally? They weren’t the size of a cat—of that he was certain. It sat on its hind legs, staring at him, drooling, beady eyes crazed.

Shadows moved in the darkness behind it, as if the rat’s shrieking called the others.

Two…six…a dozen, all of them as big as the first and some bigger, all snarling and scratching and staring and—

“Jesus Christ, Sterling!”

There was something in Mona’s voice other than her usual petulant nagging. It was fear.

He spun around, attention landing first on the car—where he expected her to be—but she wasn’t there, inside or out. Where is s—

“Who are you?”

The man who spoke was holding Mona by the arm. Not tightly. He didn’t have any weapons that he could see. Two other men approached, though—one from the left and the right.

“Sterling McBride.” He held up his hands. “I used to live here when I was a kid.”

The men traded glances. Mona was almost in tears; she didn’t even try to wriggle out of her captor’s loose grip. This is the exact scenario that likely played out in her mind when they left the interstate and took this unapproved detour. In her mind, all small towns were populated by inbred rednecks.

“I just wanted to visit, that’s all—”

“Why doesn’t anyone read the sign?” The man who held Mona groaned, more to himself than anyone present. One of his friends rubbed at the bridge of his nose, the other fell into a squat and held his head.

Sterling tried not to look at Mona. This wasn’t the time for I told you so. “Why? What does it say?”

“Do not enter. Get help.”

A leaf-scented breeze stirred debris that had gathered in the gutters. Inside the grocery door, the rats kept on shrieking, but distance muffled the sound. Small towns weren’t this quiet or empty. Not even ones whose heyday was long past. What the man had said didn’t make sense. Why didn’t these people help themselves?

“I don’t understand,” was all Sterling said.

“That’s right, you don’t.” The man flung Mona’s arm away. She ran into Sterling’s arms and he held her tight; she was so small.

The man who’d been squatting rose to his full height. “No one leaves, Sterling McBride,” he said. “Not once they cross the town line.”

News & Other WIPs

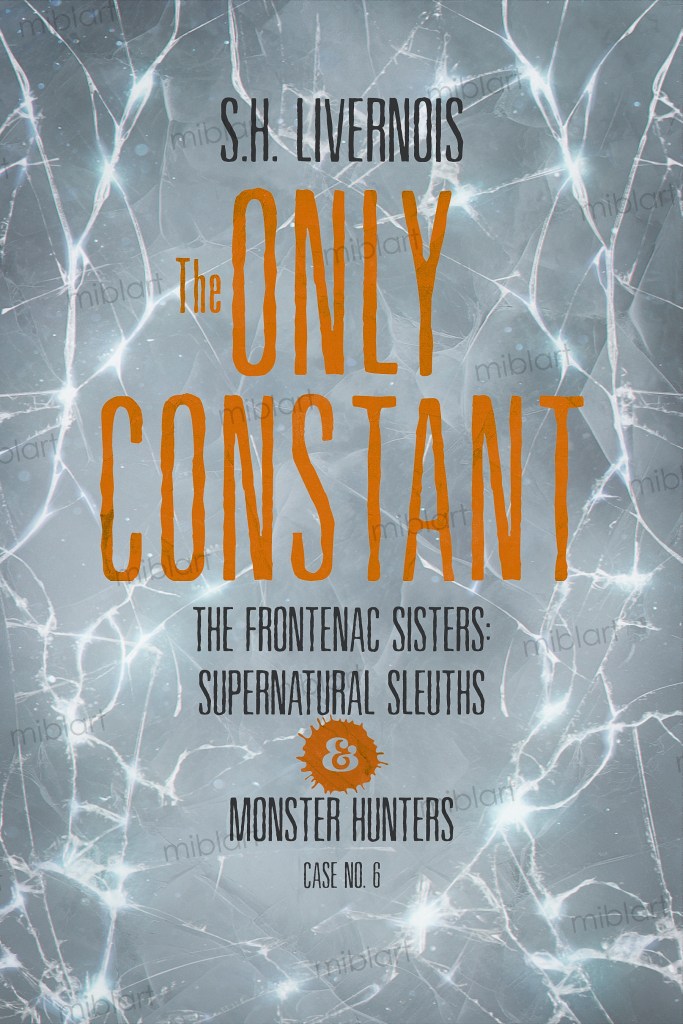

I got nothing. I’m waiting to hear back on several submissions; two of these have made it past the first pass to a final round. I won’t learn the fate of the others for a long time coming. However, what I do have is the cover of the latest Frontenac Sisters book, which I’m still writing. I’m about half-done, actually.

Leave a comment